History of the O'Brien Clan Arms: The Origin

By Garry Bryant/Garaidh Ó Briain

Heraldry was brought to Ireland with the Anglo-Normans in 1169 A.D. The Irish nobility began adapting this type of heraldry during the next couple of centuries. But Ireland was not void of heraldic symbols of their own.

Various annals tell of Irish kings and their banners with symbol and color descriptions that existed before the Anglo-Normans came. But these symbolic banners were not hereditary.

First one must understand the principle of heraldry. Its main purpose was to identify an individual on the battlefield. In time those symbols became hereditary and also associated with property, i.e., nobility. Means of differencing the basic heraldic symbol came into use to show the structure of a family and so that the symbols, although slightly modified, would show relationship to the original arms and give individual identity. The belief that a coat-of-arms belongs to all of a common surname is incorrect in the heraldry of the British Isles. Heraldic arms are granted (in the early days they were assumed) to an individual and his heirs male forever. A difference in this is in Scotland, where each individual must matriculate their arms in the court of the Lord Lyon King of Arms. [1]

Although the heraldic records of Ireland have been in existence since the first herald Sir John Chandos, K.G., in the 1300s, appointed by King Richard II. Ireland’s rules have followed those of England in most ways. The first modern Chief Herald of Ireland was Edward MacLysaght, who wrote several books on Irish family history and heraldry. The Chief Herald wrote that the basic arms of the clan did not just belong to the chief but to all clan members, and labeled them as “sept (clan) arms.” Under the Gaelic Order the clan lands belonged to the people and not to the chief. So the basic clan arms belong to the people of the clan. This position of MacLysaght has caused great debate in the circles of heraldic research, but the Chief Herald strongly wrote that one could display them on their wall to show clan membership, but if one wanted to use those arms on stationary, silver, etc., as individual arms for identity, then MacLysaght advised that that individual petition for a grant of arms from the Chief Herald’s office in Dublin.[2]

Individual arms are considered a personal matter by the herald’s office. One’s personal arms can reflect the clan arms or be totally different, which is unlike Scotland where if one has a surname of one of the Scottish clans or families, the heraldic design is based upon those of the chief’s arms. Keeping the clan or family in order heraldically.[3]

Irish heraldic arms can be found designed in three categories, lending a distinct style to Irish heraldry:[4]

1) Norman - military in origin. Use of three identical symbols. Use of

ordinaries, simplicity. (See ill. 1)

2) Anglo-Irish - Concerned with family relationships and status. Use of

ordinaries with Gaelic symbols. A main charge surrounded with

three identical but different charges. (See ill. 2)

3) Gaelic or Irish - Mythological. Use of Gaelic symbols. Simple or

complex designs. Main charge held by supporters. (See ill. 3 & 4)

Tournaments that were held in Scotland, England, and Continental Europe contributed heavily to the advancement of heraldry and its pageantry to promote the individual knight and his heraldic arms. But no tournaments were ever held in Ireland. Heraldry was used on banners and in sealing documents and property identification. One of the unique aspects to Irish heraldry is that the Gaelic symbols are also literary, they are symbols which recall to the viewer Irish mythology and the Emerald Isle’s ancient history. An example is the arm of Nuada, king of the De Danann gods, who’s hand is holding a sword. Nuadu lost his arm in battle. Because he was disfigured, Nuadu no longer could be king, and had to abdicate. The divine silversmith, Dian Cech, fashioned a silver arm for Nuadu and with magic attached it to his body making it possible for him to reclaim his kingship, which he did. The arm (or hand) holding a sword is recalling this event in Irish literature. Nuadu in old Gaelic means “cloud maker.” [5]

Other heraldic literary or mythological symbols:

Boar - Fierceness, food of the Gods.

Flaming sword - sword of light and truth.

Hand (with arm) holding sword - story of Nuada of the silver hand.

Stag - sovereignty.

Serpents and lizards - rebirth and renewal.

Hound - Myth heros of Cuchulainn and Curoi mac Daire.

Tree - kingship and druids.

Salmon - wisdom. High-Kingship of Tara.

Hand - the derbfine or true family.

Red Hand - symbol of the O’Neill's of Ulster (also the story of a king who

cut off his hand and flung it to shore to be the first to touch land

making his claim first).[6]

Cross - Christianity.

Hand holding cross - purely a Gaelic charge usually denoting the

“Kindred of St. Columcille.”

Sun, moon and stars - reaching back to pre-christian times.

The first known symbol of the O’ Brien's was the battle flag of the Dál gCais which is described in the Book of Leinster as being dung (brown), purple, red and gold (yellow). But the design is unknown (See ill. 5). The Dalcassians held the right to lead the King of Munster’s army into battle.[7]

At this same time is the banner of Brian Boru. Two sources give different designs. One design is that he used three lions, yet the other source has a blue flag with an arm holding a sword with a sun. (See ill 6.) The latter design is possibly correct.[8]

Nuadu’s arm was used by the early kings of Munster, who belonged to the Eóghanacht (MacCarthy) dynasty. These Eóghanacht kings throne name was “Mogha Nuadhad,” which translated means, “the slave of Nuada.” This dynasty set up relations with the Schottenkloster of St. James Abbey at Regensburg, Bavaria, Germany. This Irish monastery used the symbol of Nuada’s arms since many of the monks and abbots were from Munster and its benefactors were Munster kings and noblemen. The abbey arms are like that of the province of Connacht and the abbey’s arms are a dimidation of the double eagle of the Holy Roman Empire impaling an embowed arm holding a sword, i.e., the half eagle is for the Holy Roman Empire and the sword arm for the kings of Munster.[9] (See ill. 7.) When the Uí Briain’s became kings of Munster and High-Kings of Ireland in the eleventh century, this ancient Eóghanancht symbol was taken over by the Uí Briain’s and the abbey arms were used by King Conchobhar Slapar Salach Ua Briain (d. 1042 A.D.).[10] (See ill. 6.)

The Chief Herald of Ireland’s office has stated that the first heraldic arms used by the Uí Briain is described as “A dexter forearm holding a sword in pale all proper.” (See ill. 9.) This lends some continuity to Brian Boru’s banner and his grandsons use of the St. James Abbey arms.[11]

O’ Brien heraldic arms were changed on 1 July 1545, when Murrough “The Tanist” Ua Briain, 57th King of Thomond, surrendered his kingdom to King Henry VIII of England, which kingdom was re-granted to him with the English title of 1st Earl of Thomond (for life) and Baron Inchiquin (heirs male), holding all in fee simple. This resignation of Thomond to King Henry VIII took place at Greenwich by the Thames River, in England, with Murrough’s nephew, Donough Ua Briain, in tow being a minor. Donough later became 2nd Earl of Thomond and created Baron Ibrackan (his line ended d.s.p. in 1774, with the Viscounts of Clare). To show this resignation of the Gaelic Order and showing loyalty to the new king and government, the old heraldic arms were discarded and King Henry VIII granted to Murrough his own personal arms, “Gules three lions passant guardant in pale Or and armed and langued azure,” (See ill. 10) but with a difference, and lions would have no “armed and langued azure” nails and tongue. The lions would be split into the heraldic metals of gold and silver for differencing. These new arms would read as, “Gules three lions passant guardant in pale per pale Or and Argent.”[12] (See ill. 11) From an English point of view this was a great honor, but to the clan, the Irish, and the Gaelic Order, it was surrender and defeat.[13]

At this same time the name of Ua Briain (Ó Briain) was anglicized to that of O’ Brien by England, and a stop of Gaelic speech, culture, and converting to the Church of England.

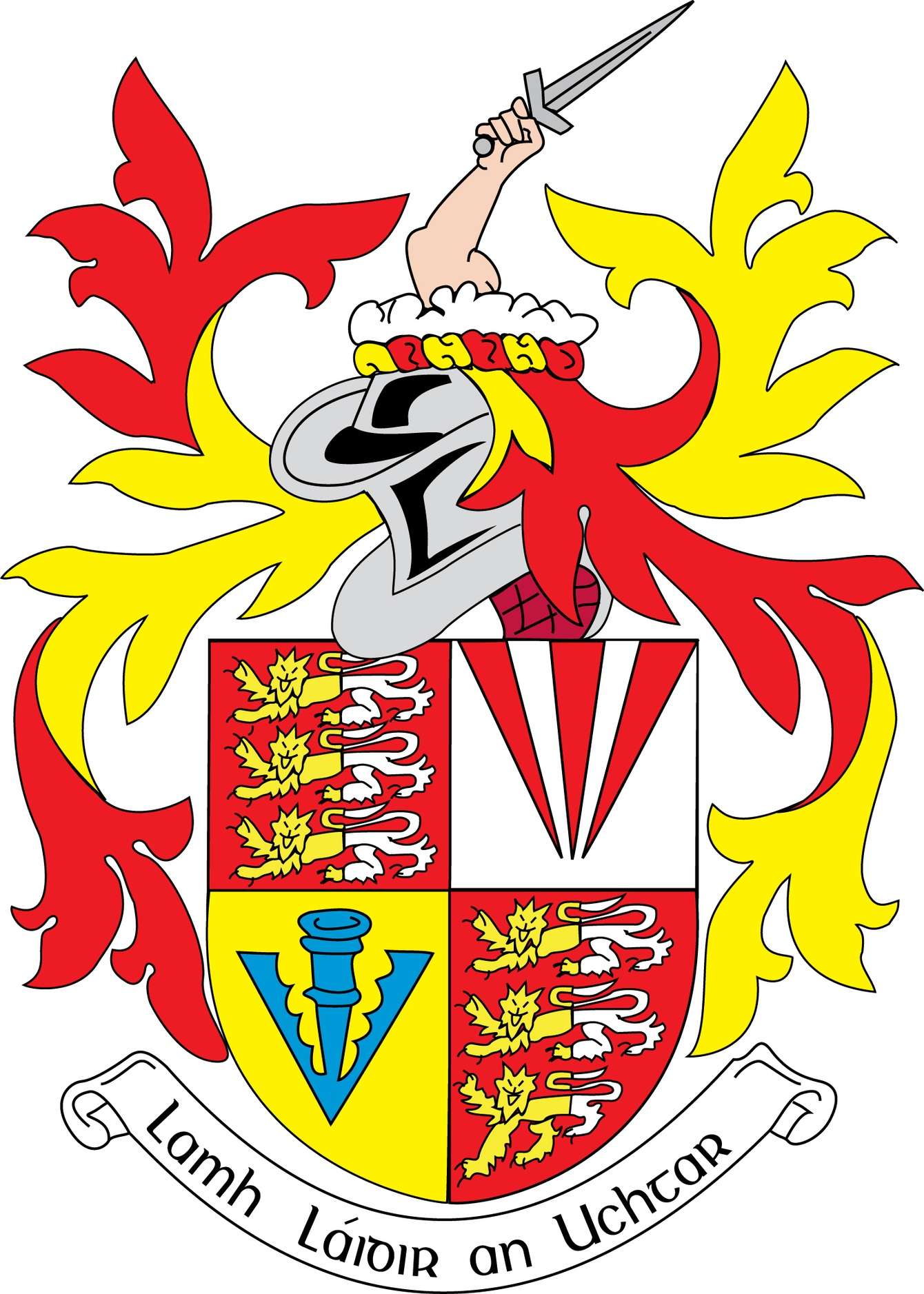

What is interesting to note, is that the ancient arms were not lost but transferred to become the crest. The only difference was the addition of clouds. This alludes to the arms Gaelic motto: “Lamh Láídir an Uchtar (the strong hand uppermost).” At this same time the O’ Brien arms became quartered with three piles. Author Ivar O’ Brien believes that this may be an earlier symbol (it first appears in 1543 as the 2nd and 3rd quarters with the lions to Murrough O’ Brien, Baron Inchiquin),[14] possibly belonging to the O’ Briens of Arra in north-west Tipperary. However there are strong circumstantial evidence that this was adopted with a difference from the Anglo-Norman family of Devonshire and Pembrokeshire, Wales. This family’s surname is de Bryan, founded by a knight named Guy de Bryan. The de Bryan’s had a branch of the family stationed in Ireland and in time they became the Marshal of Ireland. Later the de Bryan descendants settled around Dublin and heavily in County Kilkenny, and a few in County Clare. The main male line became d.s.p. in 1390 A.D., with the passing of Sir Guy de Bryan, K.G. It is speculated by Ivar O’ Brien that possibly King Brian Catha Ua Briain, King of Thomond, upon his arrival at Dublin to swear fealty to King Richard II, saw that with no male heirs of the de Bryan family, assumed the de Bryan symbol because of name similarity. The de Bryan arms are, “Or three piles meeting in base Azure.” (See ill. 13.) The O’ Brien quarter is differenced as, “Argent three piles meeting in base Gules.” In the third quarter is “Or a pheon (arrow head) Azure.”[15] (See ill. 12.)

Again only speculation to the arrow head meaning and author Ivar O’ Brien suggests that this is to show loyalty to Sir Henry Sidney, the Lord Deputy of Ireland at this time, whose personal arms used the pheon.[16]

The second motto of “Viguer du dessus,” is a poor French translation of the Gaelic motto. The French motto means, “strength from above,” which made it’s first appearance in 1615.[17] (See ill. 17.)

All this may be false according to prolific writer of things Celtic author Peter Berresford Ellis. In Ellis’ book titled 'Erin’s Blood Royal,' on page 173, is the account of King Murrough Ó Briain’s surrender of his title to King Henry VIII, and that the letters patent creating him the first Earl of Thomond has no mention of the granting of arms nor does the office of Ulster King of Arms. Ellis also has doubt that the Gaelic motto would have been authorized since it was a goal of England to erase all vestiges of the Irish language.

Then there is the tomb of Domhanall Mór Ua Briain (d. 1194) in Limerick Cathedral which bears a different coat of arms featuring a lion. There is no sign of the embowed arm holding a sword, which was an Eóghanacht crest until that time. [17a]

On a corbel next to the fireplace at Lemenah Castle, the Baronet line of the O’ Briens also carved in stone a unique Celtic knot called ‘The O’ Brien Knot.’ This badge symbol is used extensively by the Lemenah and Dromoland O’ Brien’s.[18] (See ill. 14.)

Today, The O’ Brien, Sir Conor O’ Brien, Chief of the O’ Brien Clan, has extended the use of the basic O’ Brien arms, Gaelic motto and crest for use by the O’ Brien clansmen / women and this includes the O’ Brien Celtic knot. These arms may be displayed as outlined at the beginning of this article by MacLysaght. (See cover.) Use of the quartered arms, supporters, baronet’s badge, dual motto and baron’s coronet, are strictly for use by the Chief, The O’ Brien, whose personal arms these various elements are.[19] (See ill. 17.)

The last heraldic symbol used by the O’ Brien Clan was the regimental banner of Daniel O’ Brien, 4th Viscount Clare, who commanded the Irish regiment in the service of France known as ‘Clare’s Regiment (a.k.a. Clare’s Dragoons).’ This regiment was originally organized by Charles O’ Brien, 3rd Viscount Clare, for King James II army during the Williamite War in Ireland in 1688-1690.

When King James’ army was defeated in Ireland, rather than serve the new king, William of Orange, the Irish soldiers volunteered to follow their king into exile. Many served in the armies of France, Spain and Austria. These regiments were known as ‘The Wild Geese.’ The nickname came about at the sea-ports in Ireland where on the ship manifest the cargo listed as wild geese were actually recruits for the Irish regiments abroad (France, Spain and Austria). The wild geese cargo listing was to fool the harbor-master. The wild geese continued until the units were disbanded at the beginning of the French Revolution in the early 1790s.

Uniforms for the Irish regiments in the service of France were basically white pants, shirt and knee socks, with a red coat that was trimmed in the regiments color: black for Dillon, green for Mountcashel, yellow for Clare, etc. With a matching colored vest. A black tricorn hat with a white cockade that indicated their Jacobite support.[20] (See ill. 16.)

The Clare regimental flag was quartered with a cross of St. George overall, fimbriated white. Quarters one and four were the regimental color, and quarters two and three were red. A Stuart crown was above a harp which was centered in the cross. In each quarter the crown was bendwise; sinister in quarters 1 and 4, and dexter in quarters 2 and 3. The motto, “In hoc signo vinces” is Latin for “in this sign we shall conquer.” The harp, crowns and motto were in gold.[21] (See ill. 15.)

Most of the clans that belonged to the Dál gCais have in their arms one or more lions (in variations) as displayed in the modern O’ Brien arms, but there are a few exceptions. The prolific writer, Morgan Llywelyn, has famously penned the phrase “Lion of Ireland,” which refers to Brian Boru, and does justice to him. Yet remember, the modern arms are not Gaelic or Irish at all, for their origins are with England; they are English arms, not Irish.

Dál gCais Lion

Unique among the various clans of the Dál gCais Tribe is one symbol that appears over and over again in the heraldry of the clans. The lion, particularly described as being “passant guardant,” i.e., “a lion on three legs, the right front leg lifted, and head turned to the left, facing the viewer.” However other types of lions are used, and in some coats-of-arms no lion is used at all.

This is kind off appropriate since the author Morgan Llywelyn penned the novel The Lion of Ireland, and this title has become inseparable with Brian Boru ever since.

Irish Clan Badges

While Scotland has a long history of the use of clan badges (whether plant type or heraldic), Ireland has not had any such thing. Only in the last twenty years has there developed a line of badges for the various Irish clans/families such as the ones found in Scotland.

The need for Irish clans to be represented probably has come about with the development of wearing Irish kilts. This article isn’t going to debate this development only in saying that in the early 1990s a Cornish gentleman by the name of John Kernow toured the United States speaking and educating about the Cornish people adopting the kilt and tartan to indicate to the world that the Cornish are part of the Celtic race and not English; “cool,” I thought to myself as I photographed Kernow for the local newspaper.

Last of all on the subject of Irish kilts; in the late 19th century in Ireland, the Gaelic League formed a committee to discover a native form of dress to help bring about nationalism among the people of the Emerald Isle. The conclusion was to adopt the Highland kilt with a difference, but to use one color fabric instead of tartan. So the wearing of the kilt in Ireland is over a hundred years old, worn in tartan or solid color doesn't really matter. It says to the world “We are Gaels/Celts!”

As said earlier, there was no way to tell which clan one belonged to if Irish. All that existed was wearing some kind of Celtic art jewelry, which was done in Ireland during the 19th century by the women who wanted to show their support for nationalism. This sudden surge in desire to show one’s Irish clan connections came from the Irish diaspora mainly in Australia and North America in the late 1990s. The Chief Herald’s office at Dublin Castle was silent on the subject and lent no advice on the topic.

The Republic of Ireland’s first Chief Herald was Edward Maclysaght, who wrote in one of his many books on Irish genealogy and heraldry, states that the coat-of-arms registered to the various Irish clans should be considered as “sept” arms. The arms did not belong to the chief of the clan, but to all members of the clan. This opinion does away with the rule of “one coat-of-arms to one individual.” This rule of heraldic law exists in England and Scotland, but other European jurisdictions have different rules. Maclysaght went on to state that to display the arms on one’s wall to show their membership or loyalty to the clan is proper, to use the arms as one’s own on paper, silverware, etc., then one should register to have a grant of their own.

Three different styles came about out of necessity, but they are hard to locate.

One style carried by Celtic Studio (style 1) located in North Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, has the most selection of Irish surnames, about a thousand. The badge is circular mounted by a cross that extends equally across the circle and a little off the edges. Looks like a Celtic cross, all covered by Celtic art work. On top of these is a heraldic shield of the surname’s coat-of-arms with the name above the shield. The size of the badge is 1 15/16” x 1 15/16”. Kilt pin is a sword with a shield displaying the coat-of-arms and name, very impressive looking and unique having been created by Louis Walsh in 1984, and each is hand made.

The use of the shield arms of Irish surnames is used because many Irish arms are not registered with a crest. This includes several old and prominent Irish surnames, such as O Briain, which actually has two coat-of-arms, one ancient and one modern (16th century).

A second type (style 2) of Irish badge is designed by Hilton McLaurin of Lubbock, Texas. He began his Celtic design of Scottish and Irish clans in 1995. It has many of the Irish surnames although not as many as the first. The badge is circular, with an outer ring that has the Gaelic spelling of the Irish surname on top, and in the bottom is a shamrock sided by two endless knot art. The inner circle is the coat-of-arms of the clan/family. The kilt pin is like one of the Scot styles with a sword and a circular miniature shield of the cape badge between the hilt and pommel.

The last style is probably the newest (style 3) and takes a different approach using the crest symbol of the clan instead of the shield. Thus it resembles the Scottish clan badges, but a serious detour takes place. Posted on an internet site discussing the matter was Scott MacMillan of Rathdown, Ireland, who was instrumental in designing this style of Irish clan badges. “At this same time I (MacMillan) was working with my friend Romilly Squire on several projects for Gaelic Themes in Glasgow. The Irish ‘clan badges’ seemed a natural fit, Scott Chalmers liked the idea, and the result was the present Irish clan badge offered by that firm.”

“There were two overriding reasons for not using the ‘buckle and strap’ design. First and foremost the badge had to be different than that used by the Scots-- it had to be instantly recognizable as ‘Irish’-- hence the use of the claddagh. There was also the problem that not all ‘clans’ had recognized chiefs, hence the decision to use the crest of the oldest recorded arms for each name, and to place the generic family name on the claddagh. Where no arms were recorded, the traditional shamrock/harp was substituted for the crest itself.”

One may ask “why the crest?” Unlike the shield of a coat-of-arms, the crest is not personal. Also Irish heraldry is a little different than its counterparts across the Irish Sea. There are charges that are unique to Ireland and its history that aren't found in Scotland or England.

The symbol or symbols decided upon by MacMillan and Squire was the world reknown claddagh symbol. This symbol is probably over used in many genres, but most who view it know its origins, Ireland. The claddagh is two hands holding a heart surmounted by a crown. It is said to be a 400 year old design. The hands represent “friendship,” the heart “love,” and the crown “loyalty.” Something we all need to be reminded of, and it pertains very well to the clan/family. Yet many on the Council of Irish Chiefs did not like the design because it wasn't very heraldic.

The fourth style is to have a badge designed and made independently, such as the O’ Brien Clan badge that was designed and can be found on the O’Brien Clan website.

Clan tartan

As stated earlier the Irish clans did not wear tartan, nor does it have heraldic meaning like the Scots, nevertheless, many of the Irish clans have designed, or have had designed for them, tartan. Currently two types of tartan have been designed both based on the name of the counties. The oldest version which is less than fifteen years old, are basically commercial plaids, with a general look of light colors. Personally not very pleasing. The second is only a few years old and although based on the county, the inspiration for the colors come from the coat-of-arms colors of each county and have a more pleasing look.

One of the earliest clans to have a tartan was the O’ Brien Clan. Designed in 1995 by Edward O’Brien from down under in Australia. This tartan is open to all O’ Briens to wear, but it has NOT been approved as “THE OFFICIAL” O’ Brien Clan tartan by The O’ Brien. This tartan is in modern colors, a “weathered” or lighter version in color has been woven by Dalglish mill and is an alternate version that is very pleasing.

Again, Irish clans did not wear tartan, however many have adapted a plain color be it red, blue, black, green, gray, brown, saffron, etc. The saffron colored kilt worn by the Royal Irish Rangers (an English regiment) has a burnt orange color. The reason saffron was so popular as a dye was it repelled lice.

ENDNOTES

1 The Court of the Lord Lyon, Scottish Crest Badges, leaflet #2. (Edinburgh: 1993.)

2 Edward MacLysaght, Irish Families: Their Names, Arms and Origins. (New York: Crown Publishers, 1972) Pp. 10-12.

3 John Grenham, Clans and Families of Ireland: The Heritage and Heraldry of Irish Clans and Families. (Secaucus, New Jersey: The Wellfleet Press, 1993) Pp. 72-73.

4 Lt. Col. Robert Gayre of Gayre and Nigg, The Nature of Arms. (Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd, 1961) P. 92.

5 Count of Clandermond, “Gaelic Heraldry and the Kingdom of Desmond,” Heraldry. The Augustan Society. Vol. III. 2 (1995): Pp. 4-11.

6 Donnchadh Ó Corráin and Fidelma Maguire, Gaelic Personal Names. (Dublin: The Academy Press, 1981) P. 146.

7 Proinsias Ó Conluain, “The Red Hand of Ulster,” Dúiche Néill. O Neill Country Historical Society. #5, 1990. Pp. 24-38.

8 MacMahon, Sir Lee. “Some Celtic Tribal Heraldry and Ancient Arms of Ireland,” Irish-American Genealogist. The Augustan Society: Torrance, CA. Annual 1979. Pp. 256-259.

9 Hibernian Society’s publications in the early 1900s. NOTE - Several years ago was a brief mention on the O’Brien arms stating that the three lions was in commemoration of Mileius and his slaying three lions in Africa (see John O’Hart’s Irish Pedigrees: Stem of the Irish Nation.).

10 Clandermond, p. 7.

11 John J. Kennedy, “The Arms of Ireland: Medieval and Modern,” The Coat of Arms IX. #155, Autumn 1991: London. Pp. 91-109.

12 Letter from Deputy-Herald Fergus Gillespie to Garry Bryant, 1991; Micheal Ó Comain, Irish Heraldry. (Swords, Ireland: Poolbeg Press, Ltd., 1991). P. 32-33 & 144. NOTE - the first recorded arms of an Irish prince are those of Hugh O’Neill, King of Ulster, who died in 1325. The oldest document relevant to Irish heraldry bears the seal of Roderick O’Kennedy, 1356.

13 Donough O’Brien, History of the O’Briens: From Brian Boroimhe, ad., 1000 to ad. 1945. (London: B.T. Batsford, Ltd., 1947) Pp. 50-54 & 198.

14 Ó Comain, p. 32.

15 Ivar O’Brien, “The O’Brien Arms a speculation of their origin,” The Royal O’Briens: A Tribute. 1992. P. 61.

16 Ivar O’Brien, O’Brien of Thomond: The O’Briens in Irish history, 1500-1865. (London: Phillimore, 1986) P. 16.

17 Ivar O’Brien, frontispiece.

17a Peter Berresford Ellis, Erin’s Blood Royal. (New York: Palgrave, 2002) P. 173, ‘The Munster Kingdom of Thomond.’

18 Risteard Ua Croinin, and Martin Breen “Interesting Remains at Lemeneagh,” The Other Clare. Vol/Issue 11: Pp. 46-48.

19 Meeting between Sir Conor O’Brien and Garry Bryant, 14-15 February 1997. Farmington, Utah, U.S.A.; Kennedy’s Book of Arms. (Canterbury, England: Achievements Ltd.).

20 Harman Murtagh, “Irish Soldiers Abroad, 1600-1800,” A Military History of Ireland. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996) P. 298.

21 Jane Urwick, “Banners of the Wild Geese,” The Coat of Arms, vol. IV #115, Autumn 1980: London. Pp. 285 - 289.